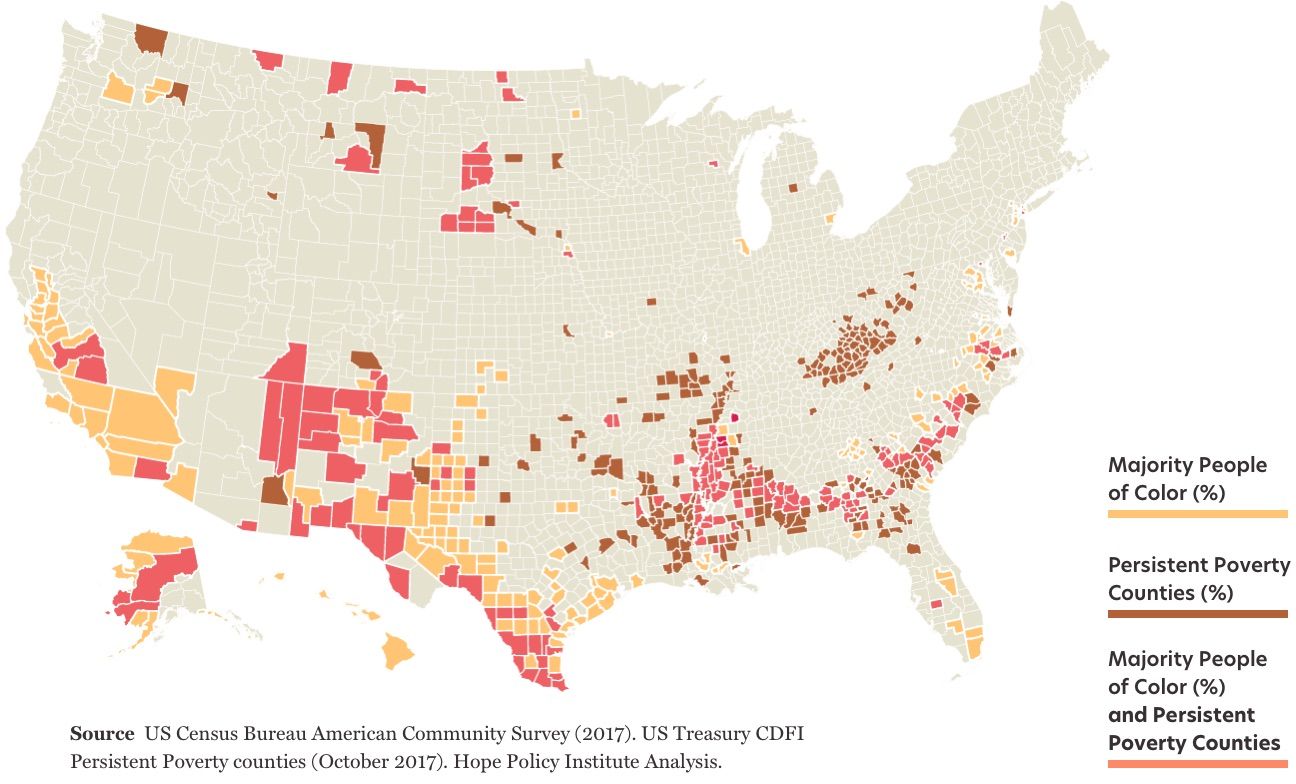

Race, place and persistent poverty are inextricably linked.

Perhaps nowhere else in the United States is the structural exclusion by race and place more self–evident than in communities of persistent poverty. Of the 395 persistent poverty counties, eight out of ten are rural. The majority (60%) of people living in persistent poverty counties are people of color. In fact, 4 out of 10 (42%) persistent poverty counties are majority people of color.

Regions of deep and persistent poverty are not an accident.

These regions were formed by policy choices that facilitated the acquisition of wealth and power among a select group through the enslavement of Africans and African Americans in the Mississippi Delta and Black Belt, the taking of land and life from tribal nations and Latinx people throughout the country and along the U.S./Mexico border, and the extraction of natural resources from Appalachia. Today, the consequences of history manifest in other forms of distress and structural exclusion – high unemployment, a lack of access to banking services and a scarcity of quality affordable housing and safe drinking water.

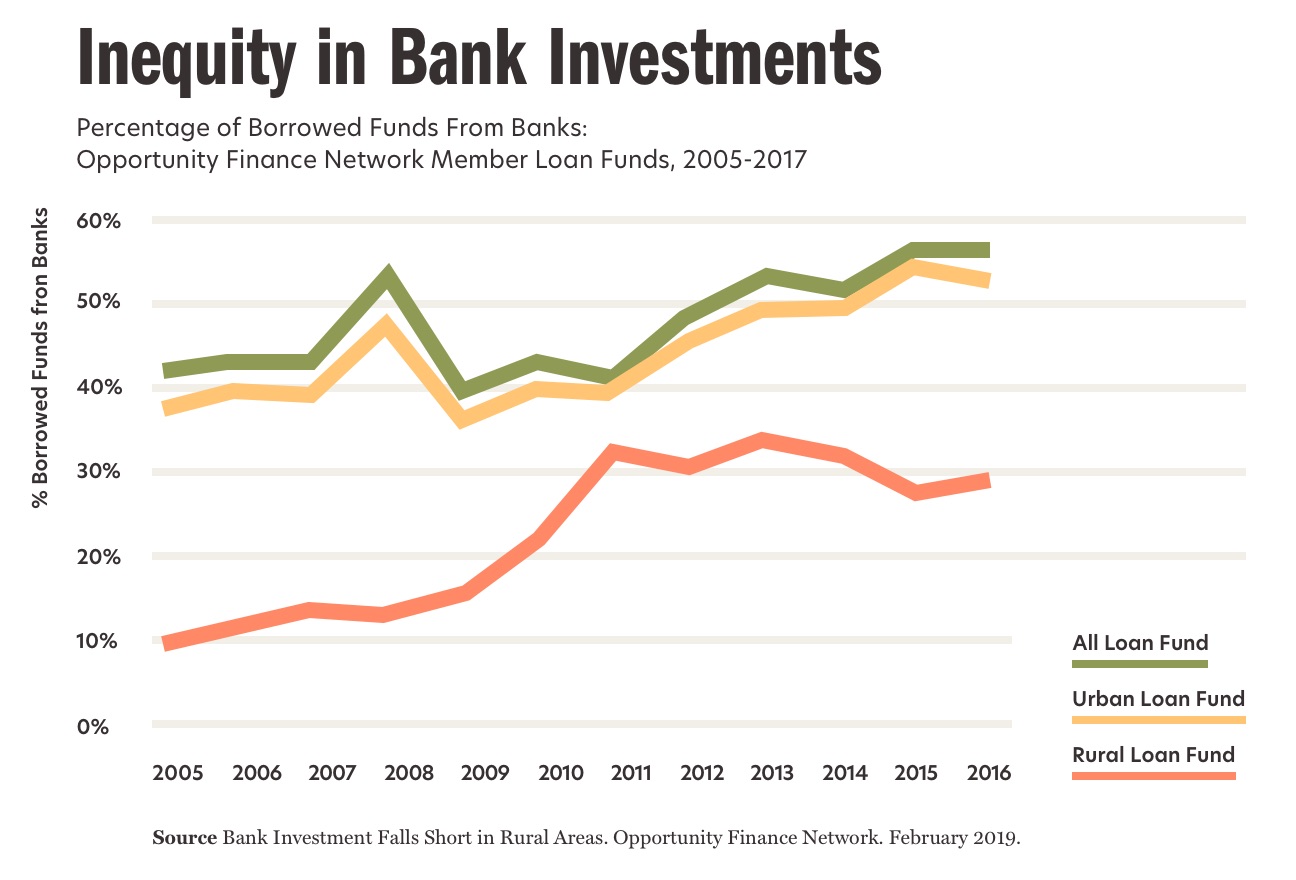

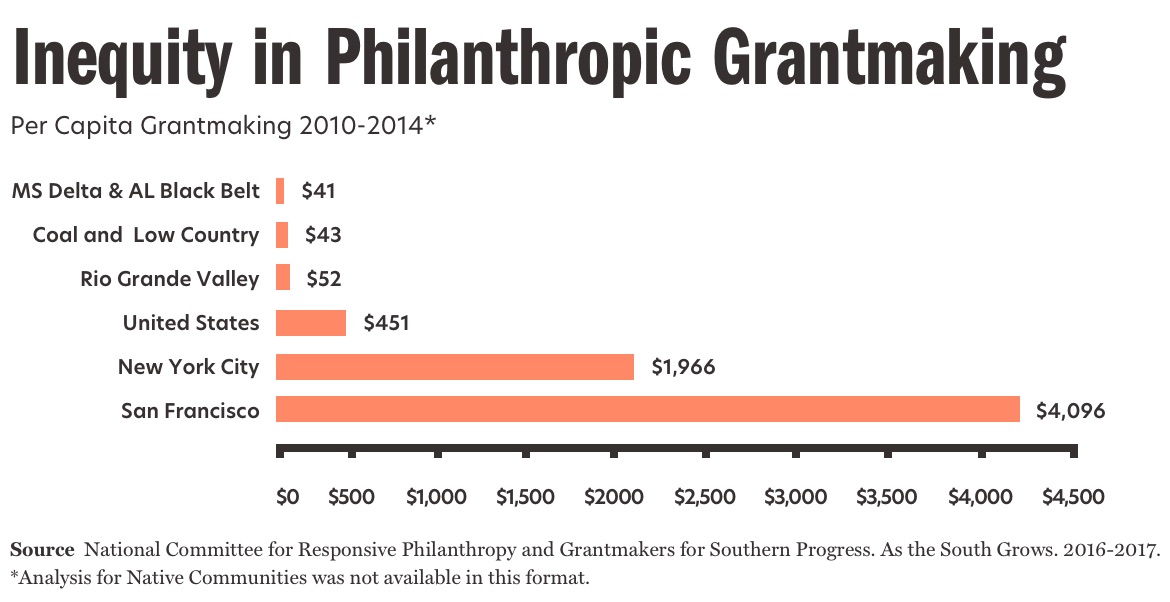

Investments lag in persistent poverty areas.

In places of great need, financial capital serves as a critical intervention. Small-business loan programs create jobs to address unemployment and poverty. Affordable housing programs offer opportunities for individuals and families to build assets through home purchase. When available, capital increases access to financial services that establish credit pathways and savings. Infrastructure development provides clean drinking water and safe disposal of waste water. Collectively, these strategies create wealth that stays in communities. We have the solutions that work but not the capital to take them to scale.

Despite the well-documented benefits of capital investment, particularly when deployed by CDFIs, regions with large concentrations of persistent poverty lag behind large urban areas in philanthropic investment and bank investment.